Worldwide, nature reserves are increasingly surrounded by “domesticated” landscapes that have been converted to housing, industry, and agriculture. But how is human activity and land use influencing ecological dynamics within these remnant wild areas? To investigate how plants in urban and natural areas interact, the Malmstrom lab worked with UC Riverside PhD student Tessa Shates (Mauck Lab) in two UC Natural Reserves near Los Angeles, California: Motte-Rimrock and Shipley-Skinner. Our team, led by Shates, found that wildland-urban interfaces expose wild plants to diseases typically found in crop plants. While the number of viruses detected in each plant varied, nearby farmlands clearly facilitated the infection of plants growing in natural reserves. The impact urban and natural interactions have on the spread of disease was further exemplified by our discovery of a tomato virus new to southern California. This particular virus is common in the southeastern United States and Mexico, and may have spread from crop plants to wild plants through the movement of agricultural products.

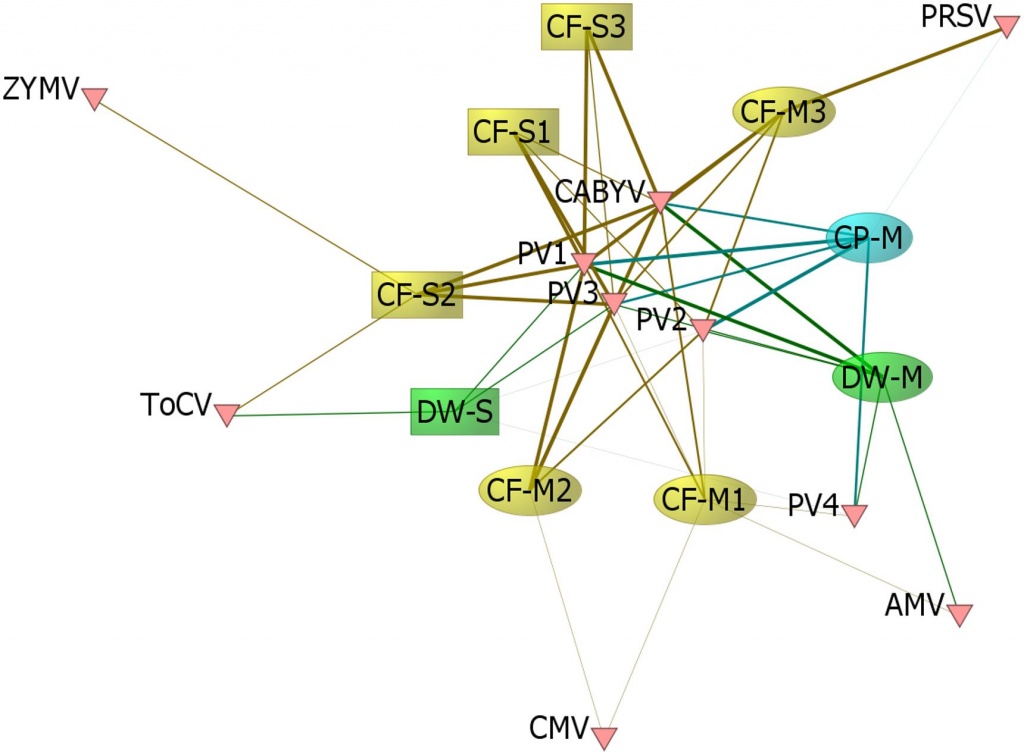

The Motte-Rimrock and Shipley-Skinner reserves contain mosaics of inland coastal sage scrub and chaparral communities. Diverse native perennial and annual plants thrive and provide habitat for rare insects and animals within their boundaries, which are clearly marked by a stark transition to industry and agriculture. The Los Angeles basin is home to around 18 million people and contains many such abrupt interfaces between urban land use, agriculture, and natural areas. While fences and roads may separate these land uses from one another, winged insects such as thrips, aphids, and leafhoppers can fly among the different vegetation types and may move viruses between crop and wild plants.

For this study, we focused on three native perennials: Buffalo gourd (Cucurbita foetidissima) and coyote gourd (C. palmata) in the Cucurbitaceae family, and sacred thorn-apple (Datura wrightii) in the Solanaceae family. Most plants in southern California grow in the rainier spring months; however, select drought-tolerant species such as those in this study grow and bloom during the summer drought. These plant populations appear as islands of green in an otherwise brown landscape, making them attractive to wayward insects moving on from irrigated, green crop fields. When these hungry insects stop to feed on wild plants, they bring with them any viruses picked up from their last meal — crop plants. Virus exchanges like this between crop and wild plants deserve more attention because they may contribute to evolution of new virus strains and emergence of novel pathogens.

Written by Ally Brown

To learn more: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2018.03305/full

Shates, T. M., Sun, P., Malmstrom, C. M., Dominguez, C., & Mauck, K. E. (2019). Addressing research needs in the field of plant virus ecology by defining knowledge gaps and developing wild dicot study systems. Frontiers in microbiology, 9, 3305.